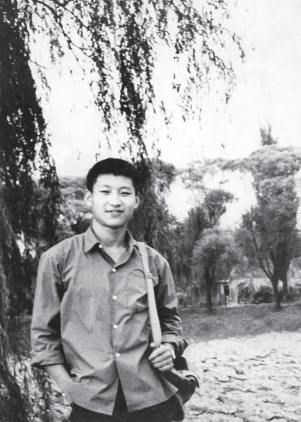

This file photo taken in 1972 shows Xi Jinping, then an "educated youth" in the countryside, returning to Beijing to visit his relatives.

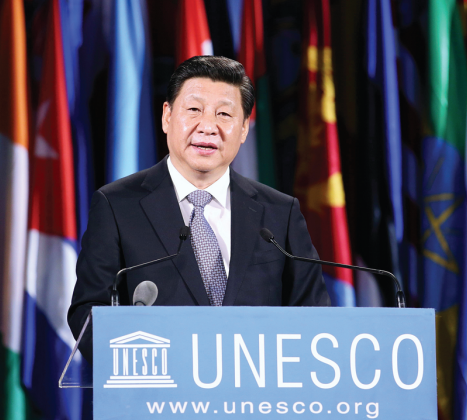

President Xi Jinping delivers a speech at the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in Paris, France, on March 27, 2014.

President Xi Jinping receives the original French version of Confucius, or the Science of the Princes, published in 1688, from French President Emmanuel Macron, as a national gift before their meeting in Nice, France, on March 24, 2019.

Xi and Macron listen to the composition High Mountains and Flowing Water, which was performed using the qin, an ancient Chinese instrument, at Baiyun Hall of the Pine Garden in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, on April 7, 2023.

Kunqu Opera artists perform in Paris, France, on Sept 13, 2023.

A pocket watch is displayed at an exhibition on Sino-French exchanges in the 17th and 18th centuries at the Palace Museum in Beijing on April 1,2024.

Every time President Xi Jinping delivers a New Year address, his office bookshelves inside the Zhongnanhai compound are studied by curious bookworms across the country and the world.

As the camera pans, careful viewers can see his collection contains quintessential French masterpieces, including The Spirit of Laws, Les Miserables, The Red and The Black, and The Human Comedy.

"I developed a keen interest in French culture and particularly French history, philosophy, literature and art when I was a young man," Xi once recalled.

He is an avid reader and his extensive reading has helped shape his global perspective.

Since taking the helm of China, Xi has made cultural interaction a trademark of his diplomacy, which has enabled a better understanding between China and the wider world.

As China and France celebrate 60 years of diplomatic ties this year, Xi is making his third state visit to the European country. All eyes will be on him, to see how this enthusiast for French culture will bring the two great civilizations of the East and the West even closer.

From Stendhal to Hugo

During his teenage years in the late 1960s, Xi, an "educated youth", was sent to Liangjiahe, a poor village located on China's Loess Plateau, so he could "learn from the peasants".

Amid the hardships of rural life, reading became Xi's spiritual solace and he consumed every literary classic he could find in the hamlet; among them The Red and The Black.

"Stendhal's The Red and The Black is very influential," Xi fondly reminisced years later. "But when it comes to portraying the intricacies of the world, works by Balzac and Maupassant are the best, for example, Balzac's The Human Comedy."

Classic books by French luminaries have made such a profound impression on Xi that he often quotes them, particularly words from Victor Hugo, in his speeches.

Addressing the landmark 2015 Paris climate change conference, Xi, in calling for a deal, cited a perceptive line from Les Miserables: "Supreme resources spring from extreme resolutions."

He also has affection for other French art, and enjoys the work of the composers Georges Bizet and Achille-Claude Debussy.

Over the years, Xi has visited several French cultural sites, from the majestic Arc de Triomphe to the opulent halls of the Palace de Versailles, and deep in his heart, he sees the timeless collections of the Louvre Museum and the revered sanctuary of the Notre Dame Cathedral as enduring treasures of human civilization.

In fact, Xi is not the first Chinese leader to have been fond of French culture. During what is known as the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement around the 1920s, the late Chinese leaders Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping both traveled to France for educational sojourns in search of a way out for China, a country that was at the time torn by war, poverty and invasions.

At the time, many patriotic Chinese youths were inspired by writings about the French Revolution, which was also the backdrop of Hugo's Les Miserables, one of Xi's most quoted French masterpieces. As Xi once recalled, one of the episodes that deeply touched him was when Bishop Myriel helps Jean Valjean and encourages him to be a better man.

"Great works possess great power to move readers," he said.

Zhiyin, or bosom friends

Xi's appreciation of French culture explains why cultural exchanges have become increasingly prominent in his interactions with French leaders and in bilateral exchanges between the two countries.

In 2019, in the French city of Nice, France's President Emmanuel Macron received Xi at Villa Kerylos, a century-old house overlooking the Mediterranean Sea that is seen as a microcosm of European civilization. There, Macron presented Xi with an ancient book: a precious copy of the original French version of Confucius, or the Science of the Princes.

Featuring a brownish, marbled calf-hide cover, a golden vignettes-imprinted spine and russet edges, the Confucian work was published in 1688, during the Age of Enlightenment. A few leaves into the book, a line of curly writing in old French reads: "To readers — the book serves as the key or introduction to reading Confucius."

The early translations of Confucian teachings inspired French thinkers including Montesquieu and Voltaire, Macron told Xi, who gently held the book with its cover flipped open.

"It is a precious gift," Xi said. Later, it became a prized part of the collection of the National Library of China.

During the 17th century, Europe witnessed the emergence of a trend known as Chinoiserie, which surged across the continent in the 18th century, fueled by increased trade with China. Concurrently, French sinologists explored the study of Confucianism, the philosophical underpinning of traditional Chinese culture, and disseminated its ideas across Europe.

Observers have noted the importance of those cross-cultural exchanges. Gu Hongming, a well-known modern Chinese scholar, wrote: "Only the French seem to understand the Chinese people and Chinese civilization best, as they have to a preeminent degree a quality of mind which, above all things, is necessary to understand the real Chinese people and the Chinese civilization."

For Xi, China and France can be zhiyin, or bosom friends, who can understand each other deeply owing to their abundant cultural richness.

During Macron's stay in China's southern metropolitan city of Guangzhou in April 2023, the two heads of state chatted over tea in the Pine Garden at the Guangdong provincial governor's residence, where Xi's father, Xi Zhongxun, had resided when he held the post in the 1980s, at the start of China's reform and opening-up.

As the two leaders strolled through the garden, the enchanting strains of qin, an ancient Chinese instrument, filled the air, weaving a captivating melody. Intrigued, Macron inquired about the name of the music. It was High Mountains and Flowing Water, responded Xi, who then shared the well-known story behind the composition, the tale of Yu Boya and Zhong Ziqi.

As the ancient Chinese legend goes, Yu was an accomplished qin player, while Zhong, his devoted listener, possessed the rare ability to grasp the emotions conveyed through Yu's music. When Zhong died, the grief-stricken Yu shattered his instrument and vowed never to play again since he lost his zhiyin, which literally means very close friend who understands the other's music.

"Only zhiyin can understand this music," Xi told Macron.

Two independents

"There is a prospect greater than the sea, and it is the sky; there is a prospect greater than the sky, and it is the human soul," Xi quoted from Hugo in his landmark speech at the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in Paris in 2014.

"Indeed, we need a mind broader than the sky as we approach different civilizations," added the Chinese president, a steadfast advocate for the harmonious coexistence of civilizations in an era of profound change in the international landscape.

Given that Paris is the host city of UNESCO and that Xi views France as a major representative of Western civilization, it is not surprising that he chose the French capital as the venue to expound for the first time his vision of civilization on the world stage.

"I vividly remember his words when he said that today (where) we live, we are representing different cultures, religions, ethnic groups, but we are part of a community of shared destiny," said then UNESCO director-general Irina Bokova. "Ten years later, none of the words President Xi pronounced has aged today. It is more relevant because of the problems we confront nowadays."

Turn the clock back 60 years to 1964. On Jan 27, China and France made history by formally establishing diplomatic relations, which shattered the icy grip of Cold War isolation and catalyzed the transformation of the global situation toward a multipolar world order. In an editorial published the next day, French daily Le Monde called the historic moment "the encounter of two independents".

In Xi's words, Chairman Mao Zedong and General Charles de Gaulle, with extraordinary wisdom and courage, opened the door for exchanges and cooperation between China and the West, "bringing hope to the world amid the Cold War".

Cui Hongjian, director of Beijing Foreign Studies University's Center for the European Union and Regional Development Studies, said, "Both China and France are independent civilizations but like-minded."

"Drawing from their rich cultures and histories, the two countries share profound insights on world trends," said Cui. "They don't want to dominate others, and in turn, they don't want to be dominated."

Laurent Fabius, president of the Constitutional Council and a former prime minister of France, said both France and China are committed to multilateralism and peace.

"In this dangerous world of ours, there must be powers of peace and sustainable development," Fabius said. "And this must obviously be, beyond our differences, a major mission of China and France."