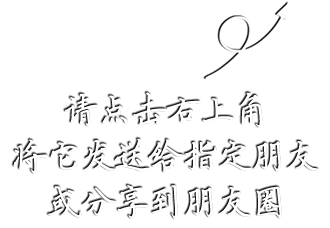

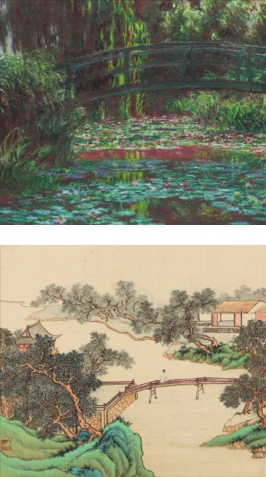

Monet's garden at Giverny, rendered in his own oil painting (top), bears an uncanny resemblance to a pictorial depiction of the Humble Administrator's Garden, believed to be the contemporary copy of an original one done by Wen Zhengming of the Ming Dynasty.

"One will always notice that as societies advance toward civility and refinement, people tend to build impressive structures before they learn to cultivate gardens with care and elegance."

This is a modern-English rendering of an observation English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon made in his essay Of Gardens (1625).

By all evidence, Bacon seems to have been right; the French admired the grandeur of the Palace of Versailles long before they celebrated Claude Monet's garden at Giverny, which, at a mere one hectare, is scarcely 1/800th the size of the sprawling estate commissioned by the all-powerful Sun King.

This pattern is evident not just in France, says Lyu Wentao, curator of Suzhou Museum's ongoing exhibition, From the Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden, in Suzhou, Jiangsu province.

"Chinese gardens began as royal and noble pleasure gardens in the first millennium BC, often built on raised earthen platforms or enclosed within defined perimeters," he says.

"Often attached to palaces and royal estates, they served not only for leisure but also for ritual and symbolic purposes, projecting the rulers' authority."

Yet, a sense of resignation eventually began emerging and quickly gained appeal among China's scholar-officials, many of whom, having experienced the inevitable disillusionment of political life, ultimately chose to withdraw from public affairs. The garden, as a miniature natural landscape, became not only their refuge but also a symbol of resilience and quiet resistance — a subtle, silent form of rebellion.

Take, for example, Zhuozheng Yuan, or the Humble Administrator's Garden, built in the early 16th century by retired Ming (1368-1644) official Wang Xiancheng. The humility he claimed to embrace was, in effect, a way of asserting moral superiority — even though his own character was somewhat open to question.

Another example is Canglang Ting, or the Pavilion of the Surging Waves, a garden that naturally took shape around a waterside pavilion. Built in the mid-11th century, it derives its name from an ancient poem composed sometime between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC.

The poem, Fisherman, declares: "If the waters of the Canglang are clear, I shall wash my tassels; if the waters are muddy, I shall wash my feet." At its heart, the verse is an allegory of a man's resolve to live by his own free will, whether in times of clarity or corruption.

Given the centrality of seclusion in Chinese literati culture, the same poem later inspired the name of another famed Suzhou garden, Wangshi Yuan, or the Garden of the Master of Nets. Here, the figure of the fisherman — "the master of nets" — became a powerful symbol of a recluse freeing himself from worldly entanglements for a life of quiet self-cultivation.

These three ancient Chinese gardens are in Suzhou, a city whose cultural sophistication rivaled its economic prominence as a trading hub from the 14th to the early 20th centuries.

Maxwell Hearn, head of the Department of Asian Art at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, believes that Chinese gardens offer tantalizing glimpses into the psyche of ancient Chinese elites and their carefully crafted self-image.

"You don't see an ancient Chinese painting in which a conquering general is planting a flag on a beach — the elite preferred to be portrayed in their own gardens," he says.

"Above all, they wanted to be remembered not as bureaucrats or governors of the state, but as gentlemen who understood the refined pleasures of painting, calligraphy, music and chess — their daily rituals."

Indeed, the "painting, calligraphy and poetry composition" hailed as the "Three Perfections" that every cultured gentleman was expected to pursue, found three-dimensional expression in the gardens themselves, where the constantly unfolding vistas evoke a long landscape handscroll meant to be savored gradually as one unrolls it.

That painterly approach is not unique to China. French painter Claude Lorrain (1600-82) was hugely influential in inspiring the English landscape garden. His luminous, idealized landscapes — with softly glowing light, classical ruins and pastoral serenity — offered a model for gardens that looked natural yet composed, blending art and nature. English garden designers, especially in the 18th century, drew on his work to create picturesque scenes that could be called "living paintings".

It is worth noting that the period when Lorrain's influence reached its height coincided with the moment when Chinese gardens and Chinoiserie began to captivate Europe through Jesuit reports, imported porcelain, and the writings of William Chambers. Out of this confluence emerged the Anglo-Chinois garden style, which married the naturalistic English landscape with Chinese accents, such as pagodas and ornamental bridges.

"Much like their Chinese counterparts, Anglo-Chinois gardens were never merely about aesthetics. They served as social and political statements, signaling their owners' intellectual refinement and cosmopolitan outlook, while also reflecting England's growing worldliness in an age shaped by global trade and cultural exchange," says Lyu.

Perhaps not incidentally, Chinese gardens also lent themselves to Enlightenment debates on the beautiful versus of the sublime that raged in Europe in the mid-to-late 18th century. Philosophers like Edmund Burke (1729-97) and later Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) defined the beautiful as pleasing, harmonious and orderly, and the sublime as inspiring strong emotional responses like awe or fear.

Seen as complementary and equally tied to human perception and moral sentiment, the beautiful in Chinese gardens was believed to have been expressed through graceful pavilions, carved bridges, tranquil ponds and framed views while the sublime emerged in dramatic rockeries, rugged "mountains", and cascading waters — features that evoked surprise, tension and wonder, aligning closely with European notions of nature's power and complexity.

"Although their Chinese counterparts may find such interpretation somewhat incongruous with their own philosophical traditions, Enlightenment thinkers were right in noting the way garden design could shape both emotion and intellect," says Lyu.

"The French Impressionists from the late 19th century shared the same fascination with nature and personal perception, with a new emphasis on the transience of time and the shimmer of light."

Of all the gardens depicted or cultivated by the Impressionists, none rivals Monet's garden at Giverny, a small village in Normandy, northern France, where the master artist settled in 1883 and began crafting his living canvas, a project that evolved over the next four decades.

"The lily pond and wooden bridge, immortalized by Monet in his light — and color-suffused canvases, inevitably evoke the spirit of an ancient Chinese garden, where water often served as the centerpiece," says Lyu, noting Monet's fascination with Japanese ukiyo-e — "pictures of the floating world" — a genre of woodblock prints and paintings renowned for their asymmetrical compositions, which provided a continual source of inspiration for the artist.

"Monet's painterly approach to his garden imbues it with a spirit remarkably akin to that of Chinese gardens — most notably the Humble Administrator's Garden, designed in part by Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), a master painter-calligrapher and a central figure in the cultural life of Suzhou."

In 1879, four years before Monet settled in Giverny, his beloved wife Camille Doncieux passed away, leaving him profoundly bereaved. In his later years, cataracts clouded his vision and altered his perception of color.

In both moments of loss and decline, the garden became his solace and refuge, a living wellspring of beauty and inspiration through which he transformed grief and trial into resilience.